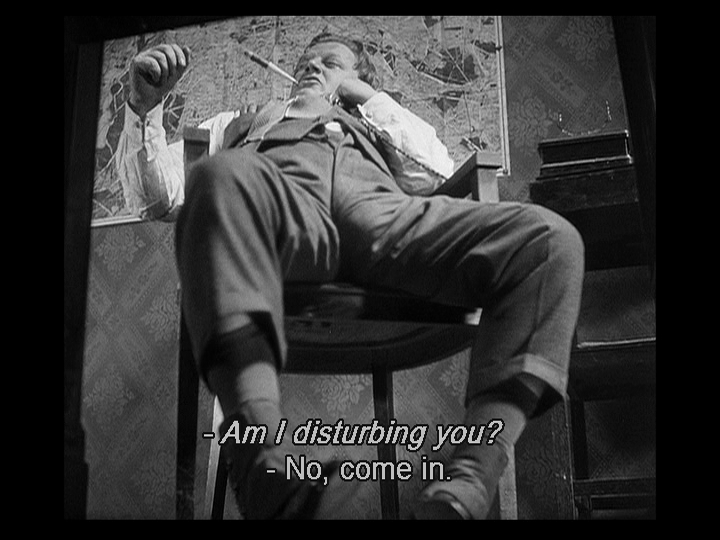

87 minutes into Fritz Lang’s 1931 thriller M (Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder), we are suddenly looking up, from beneath the desk of Inspector Karl “Tubby” Lohmann (Otto Wernicke), at the policeman’s crotch. There lies his groin, in all its non-glory, so bulgingly obvious that it is clear which way he “dresses” (to the left). And, as if what is front-and-centre needs further emphasis, Lohmann is smoking a cigarette in a long holder, making the moment all the more phallic.

The effect is jarring, as if we have suddenly been shown an upskirt-pic three-quarters of the way into this classic film noir. But this comic-grotesque scene is, in retrospect, not only entirely understandable but meant as further support—er, undergirding, if you like—for the movie’s insistence on surveillance.

Both the fish-eye-like low-angle shot and the exaggeration of Lohmann’s character here—bedraggled hair, jacket off, trousers bunched up to expose his socks and a bit of leg, that male protuberence tucked into his pants—are in keeping with M’s German-Expressionism angles and character-caricatures. Eyes pierce, expressions go agog, looks and voices can hit histrionic heights in moments of anguish or anxiety, and the murderer, Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre), is most defined by his bulging orbs.

But it is the mere fact of the camera being down there, looking up, which matters most. A crotch shot, you would think, undermines the looming Lohmann’s authority, making the policeman seem silly, he is so exposed. (If Lohmann is neglecting himself somewhat, though, it is only because he is working so hard to make up for mothers’ and the city’s neglect as girls are killed by the Murderer—Man or Monster?—in their midst.) But the effect of this low-down look is to reaffirm the camera’s ultimate authority. Amid the film’s recording- and surveillance-systems—fingerprints, identity-papers, photos, handwriting-analysis, interviews, and files are sifted through and pored over in order to track, tail, and trap—even this up-the-pants gaze is about containing and controlling by observing. The desk surrounds the camera, an effect heightened by the 1.19:1 aspect ratio, penning in Lohmann much as Beckert is about to be penned in by the underworld’s assembled kangaroo-court of a mob in the vast underground of an abandoned warehouse.

It is the camera that will sneak us in there and has snuck us in here, under this surveilling man’s desk (and it is the Mark on a sill used as a desk that helped give Beckert away to Lohmann). It is as if the Movie can go anywhere, taking us with it. We have already caught Beckert out in one of his most wretched, lustmurder-urge moments, eyeing him, in his near-convulsive fit, barely restraining his compulsion, through a trellis at a restaurant street-patio. And now, in the midst of this below-the-belt, undignified 22-second shot, Lohmann is talking on the phone about surveillance: “Listen, the whole block is surrounded. If he decides to go home, he has to run into us. So just keep on waiting.” A vast map of the city is on the wall above him; a colleague, about to relate news that will result in Beckert’s capture, has just entered. The communication- and alert-network

of the phone, the locating- and planning-network of the map, the investigation’s lead-sharing teamwork—it is all there, yet it is the tracking, watching, slipping-in-here-there-and-anywhere film-camera, this instrument of Modernity, that is meant to most thrill us. (Just four years later, as scholar Chris A. Williams and archivists James Patterson and James Taylor have noted, English police began using camera-surveillance, secretly filming street-betting from afar to crack down on the practice.)

And so the crotch shot is not meant to discomfit us at all—“Am I disturbing you?” asks the policeman entering Lohmann’s office just after we have arrived there and watch, tucked away under his desk; “No, come in,” he replies—but to reassure us and re-alert us. As M’s opening chillingly shows,

a girl in the city, Elsie Beckmann, can be so easily tracked and lured away and killed, but the serial-killer can and must be zoomed in on, watched intently, and stopped. After all, the film’s subtitle means “a city looks for a murderer” and, as film-scholar Anton Kaes notes, in this pioneering noir, “the city under surveillance has become a complex communication and information network”. It is a network to be believed in, with the camera in M the reassuring proof that no corner will be left un-watched in this systematic tracking-down of a hideous urban huntsman who must himself be caught out. Once he is captured by the authorities, and tried, and found guilty, the film’s final words come from the mouth of the murdered babe’s mother. Draped in mourning, Frau Beckmann’s distraught, wide-open eyes are as intense as Beckert’s were earlier as she proclaims, looking at the lens, “One has to keep closer watch over the children! All of you!” Then comes a fade to black; in that void, though, lingers her cry. It is a call to attention, a call for surveillance and vigilance that the camera, even in Lang’s crotch shot, echoes again and again throughout M.

Works Cited

Kaes, Anton. [BFI Film Classics:] M. Palgrave Macmillan, 2000.

M (Eine Stadt sucht einen Mörder). Directed by Fritz Lang, Nero-Film, 1931.

Williams, Chris A., James Patterson, and James Taylor. “Police Filming English Streets in 1935: The Limits of Mediated Identification.” Surveillance & Society, vol. 6, no. 1, 2009, pp. 3-9. https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/surveillance-and-society/article/view/3399/3362.

The author, a professor of film studies, has written and published this blog post for educational, critical, and analytical purposes. All film stills are included only to bolster the post’s argument and to further its educational purpose.